In

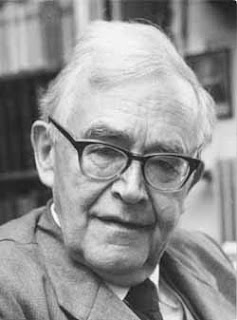

my last post I wrote of the subtlety of Hans Frei's position on the question of narrative referentiality. It's not as if “realistic narratives” do nothing more than create their own aesthetic worlds, with no intention to point beyond themselves to the “real” world outside the text. It

is possible for a narrator to refer to reality by means of a story. The question is how we are to understand the nature of this referencing and the nature of the referent. This is an issue that touches the heart of traditional Christian theology, which claims that a historical resurrection in time and space is the corner-stone of its faith.

One cannot talk of the nature of a referent without a concrete text in mind, so let's look at Frei's handling of the gospels. According to Frei, these texts are ultimately “witnesses” to the Word of God. But what is the Word of God? Is it identifiable with the concrete history of Jesus of Nazareth, the Jewish carpenter cum rabbi who was crucified in Jerusalem? Frei sees this Word as being more than (but not less than!) the “historical Jesus.” It is God incarnate, the inauguration of the kingdom, transcendence on earth, resurrection, and as such, is a reality that explodes any human categories for understanding it. How is it that any text can adequately communicate the reality of God in Christ, given the limitations of human thought and language? As Frei says,

we ... are able to think, only by way of the language in which we think. Our referencing, especially in cases where empirical objects are not involved, like God ... is language-bound. God is perhaps like us, but we also know that He is very much unlike us. Our referencing then and there is simply not ordinary referencing. (1993: 209)

So if the referent of the Gospels is one which cannot be adequately expressed by any human language, yet it is important, indeed vital, that we understand this referent, what is to be done?

Here we come to two things: the grace of God and “textuality.”

The grace of God is that the stories of the gospels are “sufficient” for our knowledge of their referent. They don't exhaust it, but they are enough for what we need, which is more than a satisfied curiosity (discipleship comes to mind). The “textuality” of the gospels, however, is the means by which that profundity is sufficiently mediated to us. Narrative is that mode of communication in which character and circumstance are intimately connected, so that if they are separated the meaning of the story is lost. The character of Jesus in the gospels is part and parcel of the narrative world of which he is a part and which contributes to the construction of his identity. Jesus, not as historical datum but as incarnate Word, is witnessed to by the narrative shape of the gospels, so that when the text references Him, it references him not just historically (e.g. using ostensive reference) but also textually (e.g. using self-reference).

This is how Frei puts it:

There is often a historical reference and often there is a textual reference; that is, the text is witness to the Word of God, whether it is historical or not. And when I say witness to the Word of God, I'm not at all sure that I can make the distinction between “witness” to the Word of God, and Word of God written. That is to say, the text is sufficient for our reference, both when it refers historically and when it refers to its divine original only by itself, textually. (ibid.)

Referencing in the gospels (and in the Bible as a whole) is no simple thing. But given the nature of the referent this should not be surprising. However we speak of God, he has chosen that we must start from the text:

that is the language pattern, the meaning-and-reference pattern to which we are bound, and which is sufficient for us.

My dialogue with John Poirier on the nature of Hans Frei's proposal goes on unabated here. In my opinion, the issue turns on the nature of the gospel, i.e. the ultimate referent or subject of the Bible. I took an hour to write a response so I'll just post an interesting quote by Hermann Diem on the relevance of history as "what actually happened" to the authors of the Gospels (I intend to start posting on "the literal sense of scripture" soon).

My dialogue with John Poirier on the nature of Hans Frei's proposal goes on unabated here. In my opinion, the issue turns on the nature of the gospel, i.e. the ultimate referent or subject of the Bible. I took an hour to write a response so I'll just post an interesting quote by Hermann Diem on the relevance of history as "what actually happened" to the authors of the Gospels (I intend to start posting on "the literal sense of scripture" soon).